Chapter 6: The Future of Agriculture

Climate change is threatening global food supplies. Our survival is at stake, but innovative technologies are transforming how we grow and secure our food.

In 2024, southern Brazil faced the worst floods in its history. Torrents of rain turned streets into rivers and farmland into vast inland seas. Bridges collapsed. Entire towns vanished beneath the water. By the time the storms subsided, hundreds of lives were lost and hundreds of thousands more were displaced.

The region of Rio Grande do Sul—home to Brazil’s agricultural heartland—was left in ruins. Power lines lay twisted across the mud, and silos once filled with grain stood half-submerged in brown water. The disaster was both environmental and economic, a stark reminder that the fuels driving global growth are also destabilizing the climate that sustains it. The cost could no longer be ignored.

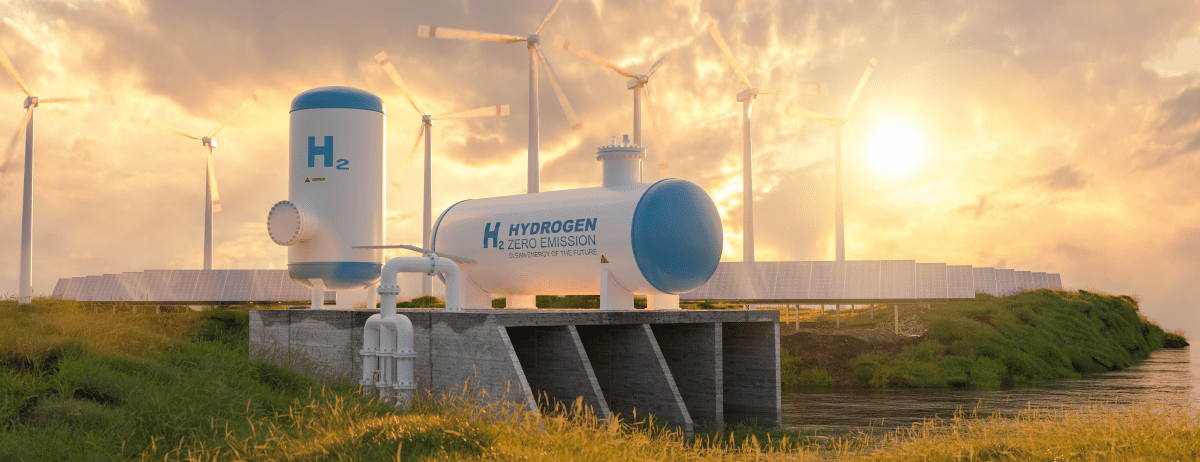

Amid the devastation, an old idea sparked a new conversation. Political leaders, scientists, and local industries reached an uncommon consensus that rebuilding must not be a return to the status quo. Instead, they looked to a different future, one driven by clean energy and anchored by an emerging technology called green hydrogen.

Green hydrogen has no carbon emissions. Meanwhile, grey hydrogen—produced from natural gas without capturing carbon dioxide emissions—emits 2.2 times what natural gas does.

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Audit Report (2022)

Made by splitting water using renewable electricity, hydrogen offered a path toward decarbonizing industries that couldn’t simply plug into the grid—heavy manufacturing, chemical production, long-distance transport, and countless other sectors that still rely on fossil fuels. What began as a regional recovery plan soon grew into a symbol of global change—nations battered by climate extremes beginning to rebuild their economies around the very solutions that could prevent the next catastrophe.

For billions of years, hydrogen has fueled the stars. It’s everywhere—woven into water, hidden in fossil fuels, scattered throughout the cosmos. The universe’s oldest and most abundant molecule could fundamentally reshape how we produce and consume energy. Yet despite its ubiquity, we’ve barely begun to use it. In a world battered by droughts, fires, and floods, hydrogen may be the bridge between survival and renewal—a way to keep civilization running without burning the planet down.

Extreme weather is no longer a distant warning. It’s reshaping economies, displacing communities, and forcing nations to rethink how they produce and use energy. Fossil fuels once powered prosperity, but now they threaten the very systems they helped build. Hydrogen offers a way out of that trap. It can decarbonize what electricity alone cannot—from the furnaces that forge steel to the engines that move goods across continents. Clean, versatile, and abundant, it stands as one of the few solutions capable of replacing fossil fuels at scale.

For all our talk of clean energy, the world still runs on combustion. Wind farms climb over desert plateaus, and solar panels stretch across rooftops from California to Shanghai, yet fossil fuels still supply more than four-fifths of the world’s energy. The smokestacks may be fewer than they once were, but their shadow still stretches across the planet.

Nuclear and geothermal energy can clean up much of our power grid, but electricity is only part of the equation. Most of our emissions don’t come from keeping the lights on—they come from how we move and how we stay warm. In 2019, roughly 15 percent of global emissions came from transportation, while another 34 percent stemmed from electricity and heat production for buildings. In the United States, natural gas use for heating and cooking accounted for 78 percent of emissions from the residential and commercial sector in 2022.

Every car engine that roars to life, every furnace that hums through the night, is part of the same system that’s heating the world. Transportation remains overwhelmingly dependent on oil. Cars, trucks, ships, and planes still burn fossil fuels at a scale we rarely stop to imagine. Across much of the northern hemisphere, millions of households still rely on fossil fuels to heat their homes. Electric heat is slowly gaining ground in new buildings, but retrofitting older homes—or relying entirely on intermittent renewable power—is often impractical.

Almost all (95%) of the world’s transportation energy comes from petroleum-based fuels, largely gasoline and diesel.

— United States Environmental Protection Agency, Global Greenhouse Gas Overview (2024)

The reality is we can’t simply electrify everything. The physics, the infrastructure, and the economics simply won’t let us—not yet.

Battery-electric vehicles are a critical part of the transition, but they are far from a complete solution. They rely on lithium-ion batteries, and lithium supplies are a finite resource. Mining and refining it is already straining global supplies and consuming vast amounts of water, often in places that can least afford the loss. Even if we could dig up enough lithium to replace every gas-powered car on Earth, we would still need staggering amounts of new electricity to charge those vehicles, run heat pumps, and power the rest of our economy.

Battery production carries its own climate cost. The lithium that powers modern EVs doesn’t arrive without consequence. Producing a single tonne of lithium releases close to 15 tonnes of carbon dioxide, long before it reaches a factory floor. Pound for pound, hard-rock lithium extraction emits over sixteen times more CO₂ than the oil extracted from Alberta’s oil sands—one of the most carbon-intensive petroleum operations in the world.

For every tonne of Australian lithium ore refined in China, about 14.8 tonnes of CO₂ are released into the atmosphere.

— Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 174 (2021)

It’s an uncomfortable paradox. We’re burning fossil fuels to mine the materials meant to replace them. And even if we solved that, our electric grids—already straining under record demand—would need to double or triple in capacity to power an all-electric world. During heatwaves and cold snaps, some regions already struggle to keep the lights on. Expanding those networks fast enough to electrify everything would require an effort on par with the post-war reconstruction era. The problem isn’t that electricity can’t power our future. It’s that an all-electric system would stress our grids far beyond what they were designed to handle.

And so we’re left searching for something that can fill the gap—a way to move energy where it’s needed, store it for when it’s not, and do it all without undoing the progress we’ve made. That’s where hydrogen begins to matter. It can be stored indefinitely, transported easily, and used in places electricity can’t reach: heavy manufacturing, chemical production, long-distance transport, aviation, and countless other sectors still tied to fossil fuels.

It can also heat our homes. In colder countries, gas furnaces are as common as refrigerators—reliable, affordable, and deeply woven into daily life. Asking millions of families to replace them overnight is unrealistic. Hydrogen offers another path. Because it burns much like natural gas, it can be blended into existing pipelines or used in modified boilers, cutting emissions without tearing out the systems people depend on.

This isn’t theoretical. Singapore has supplied homes with a hydrogen-rich gas for decades. Its manufactured “town gas” supply—a blend containing methane and up to 65 percent hydrogen—serves about 62 percent of households. Millions of people cook and heat water with a hydrogen blend every day, safely and without giving it a second thought.

For half a century, hydrogen has been hyped as the fuel of the future. For most of that time, it was a promise that never quite materialized—a technology just beyond reach, too costly or too complex to compete. But there’s another reason it never took off: fear. From the fiery destruction of the Hindenburg to the devastating power of the hydrogen bomb, public perception has long associated hydrogen with disaster. The reality is far different—modern hydrogen systems are designed to meet safety standards on par with gasoline and natural gas—but the stigma has been hard to shake.

That perception, however, is beginning to change. Countries once hesitant to touch hydrogen are now investing heavily in it. Hydrogen fleets are beginning to appear in trucking, transit, and industrial transport, while energy companies build storage and pipeline networks and governments integrate hydrogen into national decarbonization plans. After decades of false starts, hydrogen is finally stepping out from the shadow of its past.

For years, hydrogen was dismissed as impractical. Now it’s being recognized for what it can do best—produce clean energy where other fuels fall short. When hydrogen meets oxygen inside a fuel cell, the two react to create electricity and water. No soot. No carbon dioxide. Just clean power. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, a hydrogen fuel cell coupled with an electric motor is two to three times more efficient than a gasoline engine. One kilogram of hydrogen provides as much energy as a gallon of gasoline—with a fraction of the emissions.

Hydrogen’s potential in net-zero energy systems and decarbonization is gaining significant global interest. Hydrogen can be used to drive down emissions where electrification is not technically or economically feasible.

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Audit Report (2022)

The challenge has always been how to make enough of it, cheaply enough, to matter. Most hydrogen today is “grey hydrogen,” produced from natural gas through steam methane reforming—a process that releases about 900 million tonnes of CO₂ each year, roughly 180 million more than the entire aviation industry.

This process takes place in industrial reactors heated to 700–1,000 °C, where high-temperature steam breaks apart methane, releasing hydrogen—the part we want—and carbon dioxide—the part we don’t. First, methane (CH₄) reacts with steam (H₂O) to form hydrogen (H₂) and carbon monoxide (CO). Then, in a secondary reaction, the carbon monoxide reacts with more steam to produce additional hydrogen and carbon dioxide (CO₂). When that CO₂ is released into the atmosphere, the result is grey hydrogen—and it’s a major climate problem.

Blue hydrogen captures and stores up to 90 percent of those carbon emissions, while green hydrogen—made by splitting water with renewable electricity—eliminates emissions almost entirely. The science isn’t the barrier anymore. The challenge is scale—and the will to build.

Green hydrogen could be most economical in locations that have the optimal combination of abundant renewable resources, space for solar or wind farms, and access to water.

- Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen Factor, IRENA (2022)

Hydrogen’s potential is now beginning to materialize. Across the world, countries are laying the foundations of a new energy economy. Germany is linking offshore wind to hydrogen production hubs. Japan has made hydrogen central to its long-term industrial strategy. And closer to home, projects in Alberta and California are testing how hydrogen can integrate with existing energy systems. After decades of false starts, the pieces are finally coming together.

Transportation is where hydrogen’s potential becomes real. Highways, shipping routes, and flight paths still run almost entirely on fossil fuels, and replacing them has pushed engineers and policymakers to confront which technologies can actually take their place. Batteries point toward an all-electric future. Hydrogen points toward a fuel-based one. In practice, we likely need both. What matters now is matching each technology to the realities of the job.

Battery-electric vehicles have come a long way in the past two decades. They’re quiet, efficient, and dramatically cheaper to operate than gas-powered cars. The ability to plug in at home has been a game changer. For millions of drivers, that’s enough. But as the world pushes deeper into electrification, the limitations are becoming clear.

Charging takes time—sometimes hours. Range and reliability drop in winter, slowing adoption in colder climates like Canada. Battery packs are heavy, degrade over time, and depend on minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel—materials expensive to mine and harder still to recycle. And while an EV may produce no tailpipe emissions, much of the electricity powering it still comes from fossil fuels. In many regions, driving “zero-emission” simply shifts the pollution from the car to the grid.

All lithium-ion batteries degrade with use and eventually need to be replaced, and the cost of replacing an EV battery can exceed $15,000.

— Scientific American, “EV Batteries Are Dangerous to Repair” (2023)

Hydrogen fuel cells take a different approach. Instead of storing electricity, they create it. Hydrogen meets oxygen in a controlled reaction that produces electricity and water—nothing more. Refueling takes minutes. Performance doesn’t fade in the cold. And because there’s no need for massive battery packs, hydrogen vehicles can go farther without the added weight. Their only emission is a faint mist that fades into the air.

For heavy-duty transport—trucks, buses, cargo ships, even airplanes—hydrogen’s advantages add up. It’s lighter, more energy-dense, and performs consistently across distance and temperature. That matters when you’re hauling freight across continents or keeping transit moving through a prairie winter.

The key issue for hydrogen is that it’s caught in a catch-twenty-two. It lacks the infrastructure to move and store it at scale, yet there isn’t enough demand to justify private investment. For demand to grow, that infrastructure has to exist first—making it a problem that only governments can fix. For hydrogen to truly take off, it will need strong public investment and policies that make infrastructure worthwhile—and give private investors the confidence to follow. Until then, progress will come in steps, not leaps.

The rivalry between batteries and hydrogen is often framed as a zero-sum game. It shouldn’t be. Both are essential. Batteries dominate where short range and convenience matter. Hydrogen fills the gaps—long-distance travel, industrial freight, cold regions where winter slashes EV range, and regions where charging infrastructure lags behind. The future of transportation won’t be electric or hydrogen; it will be both, each doing what it does best.

Hydrogen’s potential doesn’t end on the highway. It can also help stabilize the grids that renewables depend on. When the sun sets or the wind slows, hydrogen made during peak generation can be stored for months, then turned back into electricity when needed. In that way, it complements renewables rather than competes with them. It’s the bridge between abundance and reliability—the missing link in a clean-energy system that works around the clock.

That ability to bridge systems is what makes hydrogen so promising. It’s not confined to one use or sector. The same molecule that can move freight across a continent can also keep the lights on when the wind isn’t blowing—and, potentially, heat homes without carbon.

The buildings sector represents 40 per cent of Europe’s energy demand, 80 per cent of it from fossil fuels.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP Press Release, November 2022)

Across Canada, the United States, and much of Europe, millions of homes still rely on natural gas, heating oil, or propane. Electric heat pumps are efficient and increasingly popular in new construction, but modernizing older buildings can be expensive and disruptive. For many homeowners, cost is only part of the challenge. Uncertainty plays an even bigger role—few understand how heat pumps work or what upgrades their homes might need.

Doubts about efficiency, unclear pricing, and the need for new insulation and piping, or larger radiators often discourage adoption. Furthermore, there is little point in making the switch if the electricity powering the heat pump is being generated by natural gas anyway. Even residents who can afford the switch hesitate until government grants or clear performance data make the decision easier. Hydrogen offers a potential alternative for these hard-to-convert homes. Because it burns much like natural gas, it can be blended into existing pipelines or used in modified boilers, lowering emissions without burdening families with retrofits they can’t afford.

The path forward won’t be easy. In the United Kingdom, government-backed neighborhood trials for pure hydrogen heating were shelved after strong public opposition. Residents worried about safety, costs, and being treated like test subjects. A 2024 meta-review of 54 studies found that hydrogen heating is generally less efficient and more expensive than electrification. Yet efficiency doesn’t always determine adoption. People don’t just want the best solution—they want the easiest, least disruptive one. Climate solutions won’t replace fossil fuels because it’s better for the environment, but because it feels familiar, affordable, and easy to live with.

Heat pump adoption has stalled in the UK and other Western economies due to unclear costs and efficiency benefits, required home upgrades, and limited public knowledge.

- Energy Policy, Volume 206 (2025)

Hydrogen won’t ever be the default solution for heating, and that’s fine. It doesn’t have to be. It just needs to solve the problems that would otherwise stay unsolved. In most places, that will mean hydrogen–natural gas blends in existing pipelines, starting modestly and increasing over time as infrastructure and appliances are upgraded, not a wholesale switch to pure hydrogen in every home.

Heat pumps will continue to dominate where homes are newer, grids are stronger, and retrofits make sense. But a large share of the world doesn’t look like that. Older buildings, colder regions, and communities with limited electrical capacity still need something familiar they can adopt without cutting into walls or wallets. Hydrogen fits into the systems people already use. Real change happens when solutions meet people where they are.

Hydrogen’s greatest strength is its adaptability. It can power vehicles, heat homes, and store clean energy for when renewables go dark. It can slot into the infrastructure we already have while helping build what still needs to come. It may not be the clean-energy silver bullet the world once imagined, but it’s one of the few tools that can reach the places nothing else can, keeping essential systems running when we need them most.

Hydrogen may feel like a future technology, but around the world it’s already moving from theory to reality. Nations are no longer debating whether it can work—they’re proving that it does. Projects are scaling from pilot to production, turning early experiments into the first pieces of a new energy economy.

Germany is leading with scale. The country has committed to a 9,700-kilometre hydrogen core network, much of it repurposed from existing gas lines. By 2032, that system will move clean hydrogen across borders with the same ease that oil once shaped the 20th century, linking industrial hubs, power plants, and ports across Europe. Germany isn’t just planning for hydrogen. It’s actively adapting its energy infrastructure to support it.

Japan moved even earlier. It was the first nation to publish a national hydrogen strategy back in 2017 and has spent years turning that vision into real infrastructure. Fuel-cell buses run through Tokyo. Ships and power plants are beginning to co-fire with hydrogen. For a resource-constrained island nation, hydrogen isn’t a novelty. It’s a practical way to secure energy.

Green hydrogen is projected to start competing with blue on cost by the end of the 2020s. This may occur sooner in countries such as China (thanks to its low-cost electrolysers), or Brazil and India (with cheap renewables).

- International Renewable Energy Agency, Report (2022)

Australia is reinventing its export economy. Massive hubs in Queensland and Western Australia are pairing electrolysis with solar and wind, producing green hydrogen for Asian markets. Where coal once shipped from its ports, now it will be clean fuel. “Exporting sunshine,” as some describe it.

Across Europe’s industrial centres, hydrogen is beginning to reshape the oldest emissions sources on Earth. Steelmaking accounts for up to seven percent of global emissions. Now, producers in Sweden and Germany are using hydrogen to refine iron ore, cutting out coal entirely. The smokestacks that defined the Industrial Age are giving way to pure steam.

And then there’s Canada—a country with the talent, infrastructure, and resources to lead, but not yet the vision. Alberta’s Hydrogen HUB is one of North America’s largest low-carbon hydrogen projects, yet Canadian firms often find more demand for their expertise abroad than at home. Ballard Power Systems in Burnaby, for example, designs and exports fuel-cell modules that power hundreds of zero-emission buses, trains, and heavy-duty vehicles across the world. Canadian-developed fuel-cell modules run hydrogen-powered trains in Germany and serve global public-transit fleets. We have the engineering talent, the pipelines, and the power. What’s missing is the political will to bring it all together.

Hydrogen is enjoying unprecedented momentum. The world should not miss this chance to make it an important part of our clean and secure energy future.

- Dr. Fatih Birol, The Future of Hydrogen (IEA Analysis, 2019)

Across continents, the trend is unmistakable. Countries that act boldly—Germany, Japan, Australia—are already reaping the rewards: new industries, new jobs, and a head start in the clean-energy race. Others risk watching from the sidelines as the world rebuilds around them. Hydrogen may not yet dominate the global economy, but its foundation is being poured.

These aren’t fictional stories about a future not yet realized. They’re real projects already underway. The question isn’t whether hydrogen will matter, but whether we intend to build that future here or rely on those who moved first.

Hydrogen isn’t waiting for validation anymore. It’s waiting for the decision to scale it. The science works, and the technology is proven. What stands in the way now isn’t possibility—we already know hydrogen can play a meaningful role. The challenge is sustaining the effort needed to push through the obstacles that remain. Every major transition meets resistance and must confront the weight of inertia. Hydrogen is no exception.

The first obstacle is cost. Green hydrogen—the cleanest form—is still expensive because electrolyzers remain costly and renewable power isn’t abundant enough to run them at full capacity. Blue hydrogen, produced from natural gas with carbon capture, is cheaper but controversial. Critics see it as prolonging fossil fuel dependency; supporters see it as a bridge. Both views carry truth. Until green hydrogen scales, blue hydrogen may be the only realistic way to begin replacing fossil fuels without waiting decades for perfection.

Infrastructure is the next barrier. Hydrogen doesn’t yet have the pipelines, storage, or refueling networks that gasoline and natural gas have built over a century. Without those systems, even the most advanced technologies remain isolated. Companies won’t build infrastructure without demand, and consumers won’t adopt hydrogen without infrastructure. Breaking that deadlock requires government leadership—just as highways, power grids, and rail networks once did.

Infrastructure deployment is not keeping pace with announced hydrogen projects, creating a bottleneck for large-scale adoption. Transport and storage infrastructure remains one of the most critical gaps in the global hydrogen economy.

- Hydrogen Council, Hydrogen Insights (2023)

Storage and transport add another layer of complexity. Hydrogen leaks easily, can weaken certain metals, and must be compressed or liquefied before transport. These engineering challenges are real, but not new. Industries from aerospace to refining have handled hydrogen safely for decades. What’s needed now is standardization and scale.

Public perception remains a quiet but powerful obstacle. Hydrogen still carries the shadow of the Hindenburg, despite modern systems being safer than gasoline or natural gas. People trust what they recognize and fear what they don’t. Building trust through visible success, clear safety standards, and consistent messaging will matter as much as any engineering breakthrough.

Policy inconsistency slows progress further. Rules for blending hydrogen into pipelines, certifying “clean” hydrogen, or accounting for emissions vary wildly between jurisdictions. Investors hesitate when the ground keeps shifting. Solar and wind only matured once governments set stable, long-term targets. Hydrogen needs the same stability.

The scientific evidence suggests heating with hydrogen is less efficient and more costly than electrification.

- Cell Reports Sustainability, “A meta-review of 54 studies on hydrogen heating” (2024)

Finally, there’s the question of alignment. Many environmentalists distrust blue hydrogen because it keeps oil and gas companies in the picture. Yet those same companies already own the pipelines, storage caverns, and engineering expertise needed to scale hydrogen quickly. Working with them doesn’t mean surrendering to fossil fuels. The transition will go faster if we work with them—redirecting their capacity toward something that can actually serve the transition.

None of these challenges are trivial. But they’re solvable. Solar and wind once faced the same doubts. So did nuclear power, electric vehicles, and geothermal energy. Each began as an expensive, uncertain experiment before economies of scale and policy support turned them into viable industries. Hydrogen is at that same turning point. What it needs isn’t more proof of potential—it’s the determination to follow through.

Every great transformation starts the same way—with a decision to stop waiting. Hydrogen doesn’t need another pilot project or demonstration plant. It needs scale. And scale begins with infrastructure. The challenge isn’t to prove that hydrogen works; it’s to build the systems that let it thrive.

If history teaches us anything, it’s that Canada knows how to mobilize when the moment demands it. During the Second World War, this country of just 11 million people built the third largest navy and the fourth largest air force in the world. Factories that once made cars turned out tanks and aircraft. Farms, railways, and shipyards worked around the clock. We didn’t wait for perfect conditions—we built what was needed and made the impossible routine.

It is forecasted that hydrogen could provide up to 24% of global energy demand by 2050, growing to almost 700 million tons per year.

- Journal of Pipeline Science and Engineering (2023), via ScienceDirect

That same spirit is what the energy transition requires today. The threat we face isn’t an army across the ocean—it’s here, and it’s accelerating. Floodwaters are ripping through cities. Wildfires are turning forests into ash and homes into embers. This is a destabilized climate, made dangerous by decades of neglect and delay. This isn’t a distant fight—it’s already underway. The question is whether we respond with the same urgency and resolve that defined the Greatest Generation.

Hydrogen offers a chance to build again—to invest in infrastructure at a scale we haven’t attempted in generations. The foundation has already been laid. Canada has extensive natural gas pipelines, a skilled industrial workforce, and vast clean-energy potential. What’s missing is the step from capability to commitment. That bridge will be built in two forms: Hydrogen Highways and Hydrogen Pipelines.

Transportation is one of the hardest sectors to decarbonize. Long-haul trucking, shipping, and aviation demand energy-dense fuels that batteries can’t yet match. Hydrogen can fill that gap—but only if drivers and operators can refuel as easily as they do today.

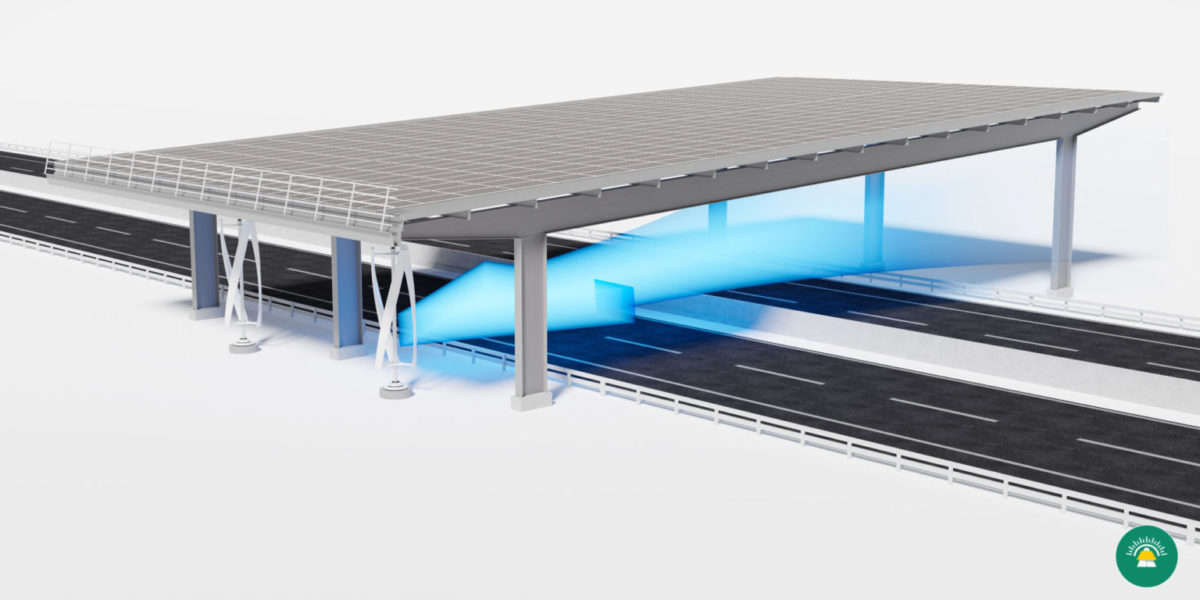

Imagine a national network of refueling stations stretching across the Trans-Canada Highway—every major corridor linked by clean hydrogen hubs. Compact electrolysis systems powered by solar, wind, or hydro could produce green hydrogen on-site, store it, and deliver it directly into vehicles. Battery charging stations can be powered the same way. These facilities wouldn’t require pipelines, tankers, or sprawling industrial complexes. Trucks hauling freight across provinces could refuel in minutes instead of waiting hours for batteries to charge. Buses, trains, and municipal fleets could run without diesel.

Picture the Trans-Canada Highway not just as a road but as a backbone for a cleaner transportation system. Major routes could host a combination of fast-charging stations for electric vehicles and hydrogen refueling stations for heavier transport. Both systems would reinforce each other. Both would make zero-emission travel feel dependable, not experimental.

Several countries are already doing this. Germany, Japan, and South Korea are already building these networks. Some countries are adding solar panels along highways. Others are redesigning sound barriers to generate electricity. These projects show that transportation corridors can be more than just roads. They can be part of the energy system. Canada could do the same, with a fraction of the $34 billion it spent expanding the Trans Mountain oil pipeline. Those hubs could become anchors for hydrogen production, storage, and research—helping regional economies pivot from fossil fuels to clean energy.

Hydrogen expands what the energy system can do. It gives us flexibility, stability, and a path toward a cleaner, more resilient future. A network that supports both batteries and hydrogen would give drivers, freight companies, and municipalities the confidence to move away from fossil fuels without waiting for perfect conditions. It would also send a clear signal that Canada intends to lead rather than follow.

Low-emissions hydrogen will remain expensive in the short term, but costs are expected to fall significantly.

- International Energy Agency, Global Hydrogen Review 2024

Both batteries and fuel cells need clean electricity to function—and highways offer the perfect real estate. Installing solar panels along the roadside could generate 2 to 6 megawatts of capacity per kilometre. That’s more than enough to power a nationwide green hydrogen refueling network using only a fraction of the Trans-Canada Highway.

At full capacity, a network of 780 green-hydrogen electrolysis stations—one every 10 kilometres—could produce enough hydrogen to refuel a Toyota Mirai over 3.4 million times. That’s tens of thousands of vehicles supported each year, even in the early stages of adoption. A coast-to-coast refueling backbone would not only enable zero-emission transport but also attract private investment and manufacturing.

The private sector can’t build this on its own. Infrastructure at this scale has always started with public vision and early investment. We didn’t wait for private companies to prove demand before building highways. We built the roads, and the market followed. Infrastructure didn’t respond to demand. It created it. The same dynamic applies now.

Refueling stations solve the problem of movement. Pipelines solve the problem of scale. If hydrogen is going to support heating, industry, and transportation across the country, it needs a reliable way to move from where it is produced to where it is used. Canada already has an enormous advantage with over half a million kilometres of natural gas pipelines that stretch across provinces and connects rural communities, cities, industrial hubs, and export terminals. Much of that infrastructure can be adapted for hydrogen with targeted upgrades.

Some lines will require reinforcement to prevent embrittlement. Compressors and valves need to be replaced. Monitoring systems will have to be improved. But these are engineering challenges we already know how to solve. Alberta, for example, has pipelines that have carried pure hydrogen safely for decades.

A hydrogen-ready pipeline network could do more than deliver fuel. It could give provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan a clear path forward—one that uses their existing expertise without locking them into a declining fossil-fuel economy. The oil and gas sector could pivot to blue hydrogen production and pipeline retrofits—keeping thousands of skilled workers employed while aligning the province’s economy with the clean-energy transition. As green hydrogen becomes cheaper, those same pipelines could carry fuel made from renewable energy. Why dismantle an entire industry when it could evolve to be part of the solution?

Canada ranks among the world’s lowest-cost hydrogen suppliers, leads in pipeline innovation, and counts Alberta among the top hydrogen-producing regions globally.

- Journal of Pipeline Science and Engineering (2023), via ScienceDirect

The potential is enormous. Pipelines could connect large-scale production sites in the West to population centers in the East. They could supply hydrogen to industrial clusters, heavy-transport hubs, and export terminals on every coast. And they could help stabilize regional grids by allowing renewable-based hydrogen to move where it is needed most.

Building this network won’t be cheap, but neither was the Transcontinental Railway or the massive buildout of Canada’s electricity system. They weren’t simply costs on a balance sheet. They were investments in the country’s future that reshaped the economy for generations. Hydrogen infrastructure can do the same—creating jobs, attracting investment, and ensuring that our energy exports remain relevant in a decarbonizing world.

Transforming an energy system is not something that happens quietly in the background. It requires direction, coordination, and a willingness to act before the path feels comfortable. The federal government can set national targets, establish regulations, and de-risk early infrastructure. Provinces can align building codes, blending standards, and industrial policy. Municipalities can electrify transit, adopt hydrogen fleets, and create early demand.

Each level of government has a role, and none of them can succeed alone. But together, they can create the conditions for private investment to follow. They can give workers and communities a sense of stability rather than uncertainty. And they can show the world that Canada intends to participate in the clean-energy transition not as a buyer of technology, but as a builder of it.

The world isn’t waiting. Momentum is already building elsewhere, and the longer Canada hesitates, the harder it becomes to catch up. Delay doesn’t preserve options—it narrows them. As demand for fossil fuels declines, postponing the transition only deepens the economic shock when that demand finally dries up. If we wait too long, we risk importing the very technologies we already have the capacity to build ourselves.

Public infrastructure spending delivers strong returns: each dollar boosts GDP by $1.43 in the short term and up to $3.83 over time, creates 9.4 jobs per $1 million invested, stimulates private investment, and recovers $0.44 through additional tax revenue.

- The Economic Benefits of Public Infrastructure Spending in Canada, Broadbent Institute (2015)

Hydrogen won’t replace fossil fuels overnight. It will scale gradually, sector by sector, supported by policies that make adoption possible rather than burdensome. But timing matters. The longer we hesitate, the harder it becomes to shape the transition on our own terms.

Canada has the capacity to act. We have the engineering talent, the infrastructure, and the resources to build something durable and valuable—not just for emissions reduction, but for long-term economic resilience.

Hydrogen can become the next major chapter in that story—a large-scale unifying effort that turns climate action into economic opportunity. We’ve done it before. We can do it again. The difference now is that delay doesn’t just raise the cost—it raises the stakes.

Hydrogen isn’t going to win every argument on efficiency. Its value lies elsewhere. It keeps options open that would otherwise disappear. It can store energy for long periods, move it across vast distances, and power sectors with few viable alternatives. That makes it one of the only tools capable of reaching parts of the system where electrification will continue to struggle.

And the debate is as much about people as it is about technology. Critics are right that using renewable electricity directly is more efficient than converting it into hydrogen. They’re also right that producing hydrogen from natural gas wastes energy and adds cost. These concerns matter. But they exist alongside another reality. Our energy system doesn’t operate on efficiency alone.

It operates in a world of jobs and livelihoods. In communities built around oil, gas, and heavy industry, people are proud of what they’ve built and anxious about what they stand to lose. Entire regional economies can’t simply pivot overnight. When the clean-energy transition is framed as a threat to people’s ability to support their families, resistance is inevitable. When people are forced to choose between environmental ideals and putting food on the table, they will choose their families every time. A transition that ignores livelihoods won’t succeed, no matter how efficient it looks on paper.

Alberta can leverage its existing natural gas reserves, renewable energy resources, extensive pipelines and energy infrastructure to play a leading role in Canada’s clean hydrogen economy.

- The Government of Alberta

The oil and gas industry won’t go quietly. It will fight to remain relevant—and in many ways, it already is, positioning hydrogen as a bridge to the future. That motivation may be self-interested, but that doesn’t mean it can’t also serve the public good. Rather than dismantling the sector piece by piece, we can redirect it. We can work with it, using its expertise, infrastructure, and workforce to build something new. The same companies that moved oil and gas can help move hydrogen. The same workers who built yesterday’s energy system can help build the next one.

Insisting on a perfect solution risks building nothing at all. That doesn’t mean settling. It means recognizing that any serious transition has to work in the real world—not just for idealists and policymakers, but for the workers, tradespeople, and rural communities that keep the country running. For all its flaws, hydrogen may be one of the most practical tools we have to bridge the gap between progress and continuity, between those pushing for rapid change and those worried about being left behind.

We won’t build a perfect energy system overnight. But if we stop treating jobs and climate action as competing priorities and focus on solutions that support both, progress becomes possible. Not because the path is easy—but because it’s workable.

Curious about why I wrote this book? Read my Author’s Note →

Want to dive deeper? A full list of sources and further reading for this chapter is available at: www.themundi.com/book/sources

Help shape the future! Sign up to receive behind-the-scenes updates, share your ideas, and influence the direction of my upcoming book on climate change.