In July 2025, nature delivered a brutal reminder of just how fast our climate is destabilizing. In South Asia, relentless monsoon rains overwhelmed India and Pakistan, washing away homes, triggering landslides, and forcing Pakistan to declare a state of emergency. In South Korea, record-breaking downpours flooded cities and displaced thousands, while Typhoon Wipha battered Hong Kong just days before landslide alerts were issued in southern China.

But it wasn’t just the storms. In Nepal’s Rasuwa district, a glacial lake burst without warning, sweeping away hydropower plants, a major bridge, and key trade routes. At least 11 lives were lost. Scientists warn that such glacial-origin floods—once rare—are now striking multiple times per year across the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region. If warming continues, their frequency could triple by century’s end.

These aren’t isolated disasters. They’re symptoms of a world built for a different climate—where roads, buildings, and supply chains weren’t designed to survive what’s coming. And while most of the conversation still centers on emissions and energy, we rarely stop to ask what we’re actually building with—and why that matters.

As the climate destabilizes, we’re beginning to confront an uncomfortable truth: the systems we’ve built—our infrastructure, supply chains, even our materials—are no longer suited to the world we’re entering. If we want to adapt, we’ll need to think not just about energy, but about the raw materials that shape our civilization. That’s not a new challenge. Throughout history, societies have relied on materials that were local, renewable, and resilient. And what if one of the most promising building blocks of a sustainable future was a plant we’ve spent the last century trying to forget?

Hemp is strong and durable, used for rope, sacks, and canvas. Its textiles can make shoes and clothing, while its fibres are used in recyclable or biodegradable bioplastics and in papermaking.

- Encyclopedia Britannica

Around 5,000 years ago, a nomadic people known as the Yamnaya left behind one of the most consequential cultural imprints in human history as they migrated west into Europe and south into India. They came from the Pontic-Caspian steppe—a vast region stretching from modern-day Ukraine to western Kazakhstan. They brought tools, horses, and language. But they also carried something else: a hardy plant from Central Asia that would follow humanity across continents and centuries. Its stalks were twisted into rope, its seeds pressed for oil and eaten for sustenance, and its fibers woven into cloth.

That plant was cannabis, and it was as versatile as it was resilient.

By the time Spanish settlers crossed the Atlantic in the 1500s, cannabis had long been a staple in Europe and Asia. One particular strain—non-psychoactive and rich in strong, fibrous stalks—was known as hemp. It became the backbone of countless industries, grown for rope, cloth, paper, oil, and more. In the Americas, it quickly became essential to colonial economies. So valued was the crop that by 1619, the Virginia Assembly passed legislation requiring farmers to grow it.

For centuries, hemp was a strategic resource. It powered navies, clothed armies, and carried knowledge across generations, scrawled on hemp paper. Then, in what felt like the blink of an eye, it vanished.

Photo Credits (clockwise from top left):

The Athabasca Oil Sands is a 760 square kilometer strip mining operation in Alberta that emits as much CO2 as 15 million cars - Environmental Defence;

Hemp was a crucial resource for rope and sails in 17th century naval fleets - Jo Dope;

Engineered Hempwood can be used as a replacement for wood-based products, including flooring, furniture, and load-bearing lumber - Hempwood;

While not a direct replacement for concrete, Hempcrete has many benefits as a construction material - IsoHemp

In the early 20th century, cannabis became collateral damage in a racially fueled political crusade. As Mexican immigrants introduced Americans to the recreational use of marijuana, public opinion soured. Lawmakers blurred the lines between hemp and its psychoactive cousin. Fueled by xenophobia and moral panic, anti-drug propaganda swept the continent. By 1937, the U.S. had effectively outlawed all cannabis cultivation, sparking a global domino effect of bans that lumped harmless hemp in with its psychoactive cousin.

Hemp’s story might have ended there—if not for World War II. In 1942, the U.S. government launched the “Hemp for Victory” campaign, briefly reviving domestic hemp cultivation to support the war effort. But the reprieve was short-lived. After the war, hemp was once again pushed aside, buried under prohibition for decades to come.

Today, that decision feels like a missed opportunity. At a time when the world is desperate for sustainable materials—when plastic pollution floods our oceans and fossil fuels still dominate global supply chains—the very plant we banned may hold some of the answers we desperately need.

Hemp won’t solve everything. But in a world drowning in plastic and choking on carbon, it might be exactly the kind of solution we should have never turned away from.

A Nation Addicted to Oil

Canada is home to the third-largest proven oil reserves in the world—trailing only Venezuela and Saudi Arabia. Most of it lies beneath the boreal forests of northern Alberta, where thick deposits of bitumen are extracted from the earth and transformed into usable fuels. Every day, around 3.6 million barrels of oil are produced from the oil sands, generating billions in revenue—and tens of millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.

The process is both energy-intensive and environmentally destructive. Extracting oil from the sands consumes about one barrel of energy for every five barrels recovered. It’s as if a 24-gigawatt power plant—larger than Alberta’s entire electricity demand—ran around the clock just to keep the operation going. But while power plant emissions are at least partially regulated and steadily improving, the energy used to extract bitumen in the oil sands is mostly burned on-site in the form of diesel and natural gas. That releases over 70 million tonnes of carbon emissions each year—equivalent to the annual output of more than 15 million cars.

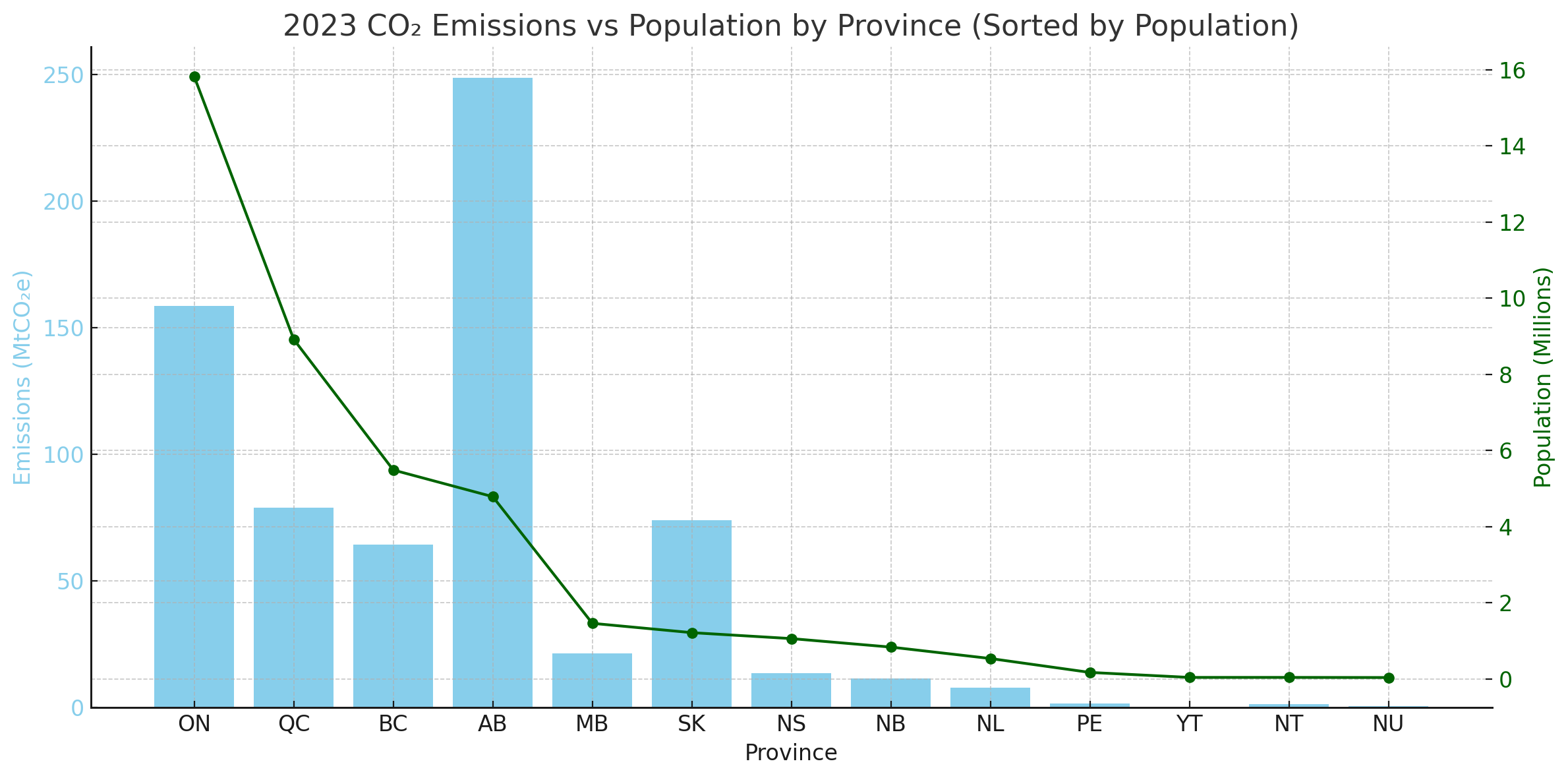

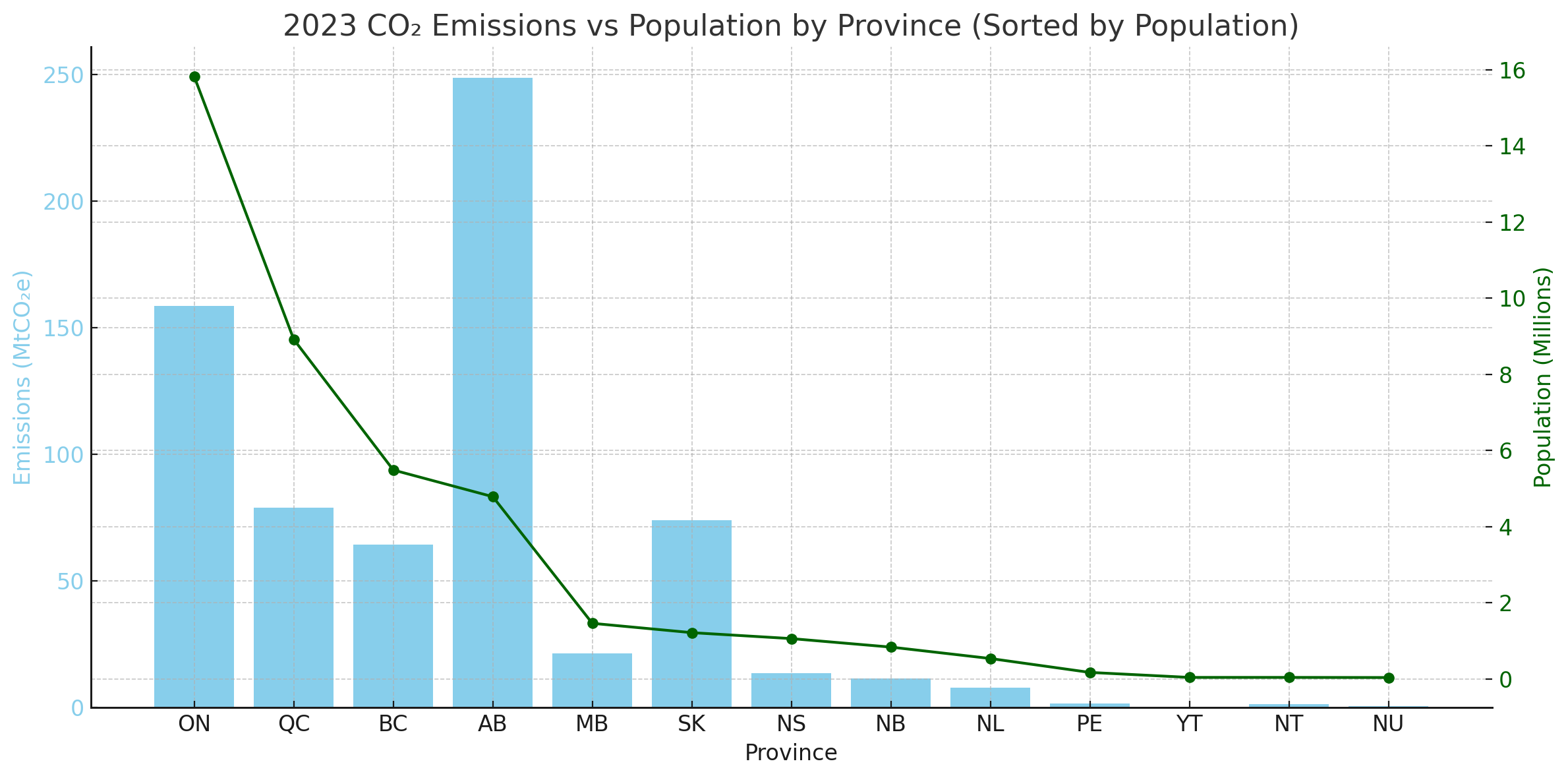

That’s why Alberta is Canada’s top emitter by far. Despite having fewer people than British Columbia, it emits more than four times as much. It also generates 70 percent more emissions than Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. Nearly 40 percent of the country’s total emissions come from Alberta—and most of that is tied directly to the oil sands.

Figure A - CO₂ Emissions By Province With Population Overlay (2023):

And yet, we can’t simply shut it all down. For better or worse, the world still runs on oil. Alternative energy sources are growing, but they’re nowhere near ready to meet global demand. Shutting down Alberta’s oil industry overnight would only reduce global emissions by less than one percent—yet it would devastate the local economy, send fuel prices soaring, and put hundreds of thousands of Canadians out of work.

Over 21 percent of Alberta’s economy is tied to oil and gas. In a province where many families depend on the industry for their livelihoods, it’s no surprise that residents fight fiercely to protect it. But the writing is on the wall. Foreign investment is drying up. The boom years aren’t coming back. Since oil prices collapsed in 2014, Alberta has permanently lost over 33,000 full-time jobs, and the sector could lose as many as 50,000 more by 2040 due to automation.

But the answer isn’t to abandon the industry. It’s to evolve beyond it. Alberta requires new sectors that are resilient, low-carbon, and economically viable—industries that can thrive in a changing world. And few are more in need of reinvention than the plastic industry. Because oil isn’t just burned for fuel. Increasingly, it’s being turned into something that never goes away.

The Plastic Problem

When we talk about oil, we usually think of fuel—for cars, trucks, ships, and planes. But a small slice of every barrel goes somewhere else entirely: into plastics. And that slice is growing.

Globally, about 10 percent of hydrocarbons are used to make plastic. It seems like a footnote—until you realize what that footnote has become. From 1950 to 2019, we’ve produced more than 9.5 billion metric tonnes of plastic. That’s over a tonne for every person alive today. And nearly all of it still exists, somewhere—buried in landfills, scattered across landscapes, or floating in our oceans.

If burning oil poisons the air, turning it into plastic poisons the land and sea. We burn most of the oil we extract, but we build our modern world from the rest—packaging, textiles, electronics, medical devices, toys, furniture, and more. It’s in our homes, our food systems, our clothes, and even our bloodstreams. And unlike fuel, plastic doesn’t vanish when it’s used. It lingers. It breaks apart. It seeps into soil, water, and the food chain, and never really goes away.

The human body is composed of 12 organ systems, and eight of them have evidence of contamination by microplastics. Atmospheric inhalation and ingestion through food and water are the likely primary routes of entry of microplastics into the human body.

- Dr. Yusof Shuaib Ibrahim et al., via Journal of Global Health (2024)

An estimated 8 million tonnes of plastic flow into the ocean every year, mostly from rivers in Asia where waste infrastructure can’t keep up with demand. Over time, these plastics break into micro-particles that choke marine life, contaminate seafood, and leach toxins into the water. Some scientists believe we’ve now crossed a planetary boundary for plastic pollution—meaning the harm we’ve caused may already be irreversible.

And we’re still producing more. Global demand for plastic is rising, not falling—driven by population growth, e-commerce, and single-use convenience. Recycling, once seen as the solution, has failed to scale. Only about 9 percent of plastic ever gets recycled, and most of that only once. The rest ends up in landfills, incinerators, or the environment—where it can take hundreds of years to break down.

We can’t recycle our way out of this, and we can’t just ban all plastic either—at least not yet. What we need are scalable, biodegradable alternatives that don’t rely on hydrocarbons. The kind of material we can produce sustainably, dispose of safely, and use to start weaning ourselves off fossil fuels.

You don’t break an addiction overnight. You replace it—step by step—with something better, healthier. And when it comes to plastic, hemp might be exactly what we need.

A Smarter Alternative

Hemp is one of the most versatile and sustainable plants on Earth. It sequesters more carbon than forests, grows in just a few months, and can be turned into everything from bioplastics to concrete substitutes. In the fight against fossil fuels, it’s not just an alternative—it’s an opportunity.

On the farm, hemp’s advantages stack up fast. It grows quickly, requires little water, and thrives in a wide range of climates. Its deep roots help prevent erosion, drawing nutrients from the soil while returning minerals and nitrogen through fallen leaves. It grows tall, fast, and dense—outcompeting weeds and reducing the need for chemical herbicides. And unlike many crops, hemp often requires no pesticides or fungicides at all.

It’s also an excellent rotation crop. When integrated into wheat farming, hemp has been shown to boost yields by 10 to 20 percent. Its regenerative qualities improve soil health, making it an asset to food security as well as industrial supply chains.

Numerous studies estimate that hemp is one of the best CO₂-to-biomass converters. Industrial hemp absorbs between 8 to 15 tonnes of CO₂ per hectare of cultivation. In comparison, forests typically capture 2 to 6 tonnes of CO₂ per hectare per year.

- Dr. Darshil Shah, Cambridge University Researcher, via Dezeen (2021)

Hemp’s carbon performance doesn’t stop with farming. It can be used to remediate polluted soils, drawing toxins out of contaminated land while continuing to sequester carbon at high rates. A single hectare of industrial hemp can absorb up to 22 tonnes of carbon dioxide in just one season—nearly four times what mature forests absorb in a year.

And then there’s what we can do with it. Roughly 60 to 70 percent of hemp’s stalk is cellulose—the foundation for bioplastics and paper. The inner core contains lignin, a natural binder. It can replace bitumen in road construction and petroleum-based adhesives in building materials. In a world trying to replace carbon-intensive concrete and petrochemical plastics, hemp offers real, ready-made alternatives.

One of the most promising applications is hempcrete—a composite made from hemp hurd and lime. It’s not load-bearing, but it’s lightweight, fire-resistant, mold-resistant, and carbon-negative. In France, hundreds of homes have already been built using this material.

Lime hemp concrete is a carbon-negative building material made from hemp and lime. Research shows it can sequester over 300 kilograms of CO₂ per cubic meter.

– Tarun Jami, Gujarat Forensic Sciences University, via ResearchGate (2017)

And it works on a far shorter timescale than forest-based solutions. Trees take decades to mature. Hemp is ready for harvest in three to four months. It can produce four times more pulp per acre than trees over a 20-year cycle—and its paper can be recycled more often, with a longer shelf life.

Few crops offer as wide a range of uses. Hemp’s fibers are among the strongest in the plant kingdom, perfect for textiles, rope, and canvas. It can be turned into biodegradable plastics, high-protein food products, biofuels, cosmetics, animal bedding, building insulation, and more. Nearly every part of the plant has value.

So why isn’t hemp everywhere? With all this potential, you’d expect it to be booming across Canada. But the reality tells a different story.

Facing the Challenges

Industrial hemp has long been championed as a crop of the future—versatile, sustainable, and rich with economic promise. Yet in Canada, its recent trajectory tells a different story. In 2019, farmers planted over 72,000 hectares of hemp nationwide. By 2023, that figure had fallen to just 15,588 hectares—an almost 80 percent drop in only four years.

So what happened? The problem isn’t hemp—it’s the system around it. Policy gaps, missing infrastructure, and incentives that work against farmers turned early enthusiasm into a slow collapse.

This wasn’t the result of farmers losing faith in hemp’s potential. After the 2018–2019 boom, Canada faced an oversupply of hemp grain and biomass, pushing prices down and cutting into farm incomes.

At the same time, the country lacked large-scale fiber mills, seed oil processors, and bioplastic plants—facilities needed to turn raw hemp into high-value products. As a result, most of the harvest was relegated to low-margin commodity markets. With no reliable buyers, many farmers shifted back to proven staples like canola and soybeans.

Industrial hemp continues to be subject to U.S. drug laws, and growing industrial hemp is restricted. Approximately 30 countries in Europe, Asia, and North and South America currently permit farmers to grow hemp.

- U.S. Library of Congress, via Hemp as an Agricultural Commodity (2018)

Legal and political baggage compounds the problem. Even though industrial hemp contains almost no THC—the psychoactive compound in cannabis—it remains entangled in outdated laws and cultural stigma. In some countries, cultivation is heavily restricted or outright banned. In others, laws are unclear or inconsistently enforced, making it harder to build stable international markets and harder for investors to commit to long-term growth.

Even in Canada, where hemp is legal and regulated, development has been slow. High processing costs, lukewarm government support, and shifting regulations have made it difficult for the industry to scale.

The result is a promising crop trapped in a niche role on the global stage. But it doesn’t have to stay that way. We’ve seen how quickly targeted policy can transform entire industries—from wind and solar to electric vehicles. With the right combination of processing investment, stable purchase agreements to give farmers confidence, and a clear national strategy, hemp could follow a similar path. Overcoming these obstacles wouldn’t just stabilize the industry—it could unlock an entirely new pillar of Canada’s economy.

A Path to Economic Renewal

Alberta is standing at a crossroads. It can double down on a fading oil economy—or use its resources, talent, and land to build the industries of the future. Industrial hemp could be one of them.

To unlock hemp’s potential, we need to close the structural gaps holding the industry back—from missing processing facilities to outdated policies. Alberta’s economy, still heavily tied to oil and gas, risks falling behind as the world moves away from fossil fuels. Clean energy alone won’t be enough. The province also needs new industries that can grow in parallel—industries like industrial hemp.

In 2021, Canadian farmers planted roughly 22,000 hectares of hemp. Cultivation has dropped sharply in recent years, but the long-term potential is enormous—especially as global markets shift toward low-carbon, renewable materials.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development estimates the global hemp market could reach nearly $19 billion by 2027—nearly four times its 2020 value. The bioplastics market is growing even faster, expected to soar from $11 billion in 2022 to $46 billion by 2030. That demand could fuel an entire supply chain of farming, processing, manufacturing, and exports—industries perfectly suited to regions like Alberta, where infrastructure, land, and technical expertise are already in place.

Hemp is a low-carbon and environmentally sustainable product that sequesters carbon dioxide and can be used to produce biodegradable plastics, textiles, construction materials, and biofuels.

- UNCTAD, via Commodities at a Glance: Special issue on industrial hemp (2022)

Even at the farm level, the economics can be compelling. Back in 2017–2018, according to the Government of Alberta, dryland hemp crops were earning around $400 per acre in net profit, with irrigated fields approaching $750. For comparison, canola—Canada’s most widely grown crop—averaged less than $45 per acre in profit at the time.

Those margins have narrowed as supply has grown, but hemp still offers something most commodity crops don’t: multiple revenue streams from a single harvest. Seeds, fiber, and hurd can each be sold into different industries—from textiles and bioplastics to construction materials and animal bedding—helping stabilize farm income even when market prices fluctuate.

This is a chance for Alberta to diversify without abandoning its economic strengths. The province has the farmland—over 20 million hectares—much of it suitable for hemp cultivation. It has industrial know-how, logistics infrastructure, and a culture of innovation. What’s missing is processing capacity, targeted investment, and a coordinated vision for scaling up.

Because of its versatility, the industrial hemp market holds vast potential in agriculture, textiles, recycling, automotive, furniture, food and beverages, paper, construction materials and personal care.

- UNCTAD, via Commodities at a Glance: Special issue on industrial hemp (2022)

Alberta doesn’t need to abandon the oil sands overnight—and realistically, Canada can’t afford to until we’ve built viable alternatives. But the province can start building the next layer of its economy: one that’s more resilient, more sustainable, and ready for the future.

Canada has spent decades exporting raw resources while importing finished goods, hollowing out its manufacturing base in the process. Hemp offers the chance to break that cycle. Because the industry is still young, we can build value-added manufacturing here at home—from bioplastics to textiles to building materials—rather than shipping raw hemp abroad. With the right investment, Canada could move from supplier to global leader in the low-carbon products the world is searching for.

Hemp won’t replace the fuels that power our economy—but it can replace something just as pervasive: the materials we make from oil. From packaging to pavement, hemp-based alternatives are already being tested around the world. Canada has the resources, expertise, and capacity to lead this shift—showing, in practical terms, what a post-petroleum economy can look like. And many of the biggest opportunities aren’t in energy, but in the products and infrastructure we use every day.

Replacing Plastics and Paving Roads

Moving beyond oil will take more than replacing what we burn—it will require rethinking what we build. Plastics and asphalt may not be as visible in the climate conversation as pipelines or tailpipes, but they’re major products of fossil fuel extraction. And in both cases, hemp offers real, tangible alternatives.

Take bioplastics. Since hemp is made up of 60 to 70 percent cellulose, it’s an ideal feedstock for biodegradable plastics. Unlike conventional plastics, which persist in the environment for centuries, hemp-based bioplastics can break down naturally—sometimes in as little as six months under the right conditions. They’re non-toxic, renewable, and don’t rely on petrochemicals. Most of today’s bioplastics are still produced from corn or sugarcane. But hemp is gaining ground for its superior fiber content and lower environmental footprint.

Plastics currently account for 10% of global oil production. With single-use plastics accounting for just over a third of plastics produced globally in 2017.

- Professor Michael Jefferson, via Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 56 (2019)

Roughly 10 percent of the world’s oil and gas is turned into plastic. Alberta’s oil sands produce over a billion barrels of oil each year, which adds up to around 17 million tonnes used for plastic production. Replacing that with hemp-based alternatives would require about 5.7 million hectares of land—around 9 percent of Canada’s total farmland. It’s ambitious, but achievable—if we rethink how and where we grow our food.

Dedicating millions of hectares to hemp may sound like a disaster for land use. But that assumes agriculture will never evolve from its current form. Advances like vertical farming and controlled-environment agriculture allow us to grow more food with far less land, water, and pesticide use—freeing up traditional farmland for crops like hemp. In the long run, it’s not a zero-sum game. We just need to be smarter about how we use the land we’ve got.

Land use is only half the story. The other is finding high-impact applications—like infrastructure—where hemp could replace oil entirely.

It is estimated that 85 % of all the production of bitumen, amounting approximately to 100 million tonnes per year, is destined for the road infrastructure sector.

- Dr. Elena Gaudenzi et al., via Construction and Building Materials, Volume 362 (2023)

The inner core of the hemp stalk, called the hurd, contains high amounts of lignin—a compound that gives plants their stiffness. Lignin happens to share similar binding properties with bitumen, the petroleum-based glue used to make asphalt. The Netherlands has already paved more than two dozen test roads with hemp-based “bio-asphalt”. They’re holding up under traffic, and early results suggest they might even outlast conventional asphalt—all while slashing emissions.

Realistically, hemp can’t replace the bulk of our oil consumption, especially in transportation and energy. But that’s not where its greatest value lies anyway. Only a small percentage of every barrel of oil is used for plastics, asphalt, and industrial feedstocks. And it’s precisely that slice—the durable goods and building materials we rely on every day—where hemp can have the biggest impact.

We don’t have to replace every drop of oil to break our dependence on it. We just have to start with the parts that no longer make sense—and for those, hemp may be one of the smartest tools we have, if we invest in the systems to make it possible.

Growing the Future

Hemp isn’t a magic solution. It won’t eliminate fossil fuels or solve climate change on its own. But it doesn’t need to. What it offers is something more strategic: a way to chip away at our dependence on oil—one product, one field, one industry at a time.

It sequesters carbon faster than trees. It grows with minimal inputs and helps regenerate the soil. It can clean up contaminated land and strengthen rural economies. Its fibers can replace plastics, wood pulp, textiles—even bitumen. Nearly every part of the plant has value—and nearly every part of our economy has a place for it.

For provinces like Alberta, that flexibility could mean the difference between decline and renewal. It gives us options. It builds resilience. And it offers a way to rethink not just how we power our world—but how we build it.

As interest in hemp grows globally, there is an opportunity to build a new model of fiber production—one that prioritizes regeneration, equity, and climate resilience from the start.

- Textile Exchange, Growing Hemp for the Future: A Global Fiber Guide (2023)

Canada is well-positioned to lead this transition. We have the farmland. We have the infrastructure. We have the talent—and the policy frameworks to move quickly, if we choose to. Hemp could become a cornerstone of a low-carbon export strategy, a driver of jobs and investment, and a practical tool for meeting our climate goals without leaving workers or provinces behind.

But that won’t happen on its own. It will take investment, coordination, and a willingness to treat hemp not as a novelty crop, but as a strategic industry of national importance. It will take the kind of leadership and long-term vision that’s often missing from politics today.

What we choose to grow won’t just shape our fields. It will help shape our future.

Curious about why I wrote this book? Read my Author’s Note →

Want to dive deeper?

A full list of sources and further reading for this chapter is available at:

www.themundi.com/book/sources